|

Court Acts to Halt Dumping Invasive

Species in U.S. Waters

SAN FRANCISCO, California, April 4, 2005 (ENS) - Ship ballast water can no longer be

dumped in U.S. ports without a permit, a federal judge in

California has ruled. Invasive species - such as zebra mussels

and Chinese mitten crabs - hitchhike in the ballast water of

ships entering U.S. ports from around the world. The exotic

aquatic plants and animals enter U.S. waters when the ships

discharge water taken on as ballast to adjust their weight

when cargo is loaded.

In a lawsuit brought by environmental groups concerned

about the release of invasive species into U.S. wasters, Judge

Susan Illston ruled Thursday that the U.S. Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA) must repeal a regulation exempting

ships that discharge ballast water from the permit

requirements of the Clean Water Act.

Judge Illston found that the EPA "acted in excess of its

statutory authority" by exempting ballast water discharges

from the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination Systems

(NPDES) permit program. "EPA did not have authority to exclude

categories of point sources from NPDES permit program," the

judge wrote.

Ship discharges ballast water that may have invasive

aquatic species from across the globe. (Photo courtesy

NBIC) Plaintiff groups -

Northwest Environmental Advocates, the Ocean Conservancy, and

Waterkeepers Northern California and its projects Center for

Marine Conservation and San Francisco Baykeeper and

Deltakeeper - were pleased with the ruling in their

longstanding case against the federal agency.

"Over 30 years ago EPA made a grave error in failing to

regulate the indiscriminate dumping of invasive species along

the nation's coasts and the Great Lakes, an error it

compounded when it refused to grant our petition over six

years ago," said Nina Bell, executive director of Northwest

Environmental Advocates based in Portland, Oregon.

Environmental groups first petitioned EPA to regulate

ships' ballast water discharges in 1999 because ballast water

is the nation's largest source of aquatic invasive species.

After having been forced through an initial lawsuit to answer

the groups' petition, the EPA denied it in September 2003,

"Today we're extremely gratified by the court's ruling,

which brings the requirements of the Clean Water Act to bear

on preventing new invasions. It's a shame that EPA requires a

court order to comply with federal law," Bell said.

The Earthjustice Environmental Law Clinic at Stanford

University and Pacific Environmental Advocacy Center at Lewis

and Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon, represent the three

organizations.

"This is a decisive legal victory," said Deborah Sivas,

director of the Earthjustice Environmental Law Clinic at

Stanford said. "It will provide protection against invasive

species in hundreds of bays, rivers and streams throughout the

country and in our coastal waterways."

A tanker ship in the Great Lakes can contain as much as 14

million gallons of ballast water, which would be discharged at

port when the ship takes on cargo. Seagoing tankers can have

double the amount of ballast water. The amount of ballast

water discharged in this country’s waters exceeds 21 billion

gallons each year.

The EPA did not respond to calls for comment. The agency

states on its website that the introduction of invasive

species through ship ballast water is "a major concern."

"All mainland coasts of the United States – East, West,

Gulf, and Great Lakes, as well as the coastal waters of

Alaska, Hawaii, and the Pacific Islands – have felt the

effects of successful aquatic species invasions," the agency

website states.

The Chinese mitten crab may have been illegally introduced

to San Francisco Bay in 1992-94 as a food resource. It burrows

into and weakens dikes and levees and is a host to the

oriental lung fluke, a human parasite. (Photo courtesy

USGS) "Over two-thirds of recent non-native

species introductions in marine and coastal areas are likely

due to ship-borne vectors, and ballast water transport and

discharge is the most universal and ubiquitous of these. EPA

is working in conjunction with our Federal and State partners

to address this source of aquatic invasive species both

domestically and internationally," the agency states.

Sarah Newkirk, clean oceans advocate for The Ocean

Conservancy said, "Invasive species carried in ships' ballast

water have measurable impacts to businesses, taxpayers and the

environment. They harm commercial fishing and shellfishing,

clog the intake pipes of power plants and drinking water

treatment facilities, destroy habitats and push threatened

species to the edge of extinction."

"It's high time EPA placed the burden of controlling

invasive species on those who create the problem," Newkirk

said.

In her ruling Judge Illston cited a study by the

investigative arm of Congress, the Government Accountability

Office (GAO), which said “more than 10,000 marine species each

day hitch rides around the globe in the ballast water of cargo

ships.”

"Invasive species transported by ballast water have taken

over wetland habitats, and deprived waterfowl and other

species of food sources," the GAO report says.

There are many invasive aquatic species in the San

Francisco Bay and San Joaquin Delta, the largest estuary

system on the U.S. west coast and one of the world's busiest

international ports.

"The Bay-Delta estuary is a poster child for the harm

caused by invasive species carried in ballast water. It is the

most invaded estuary in North America and possibly the world,"

said Leo O'Brien, executive director of Baykeeper.

"The invaders like the Asian clam, the green crab, and the

Chinese mitten crab now dominate the native species and it's

getting worse: on average a new species establishes itself in

the Bay every 14 weeks," said O'Brien. "Hopefully the tide is

now turning."

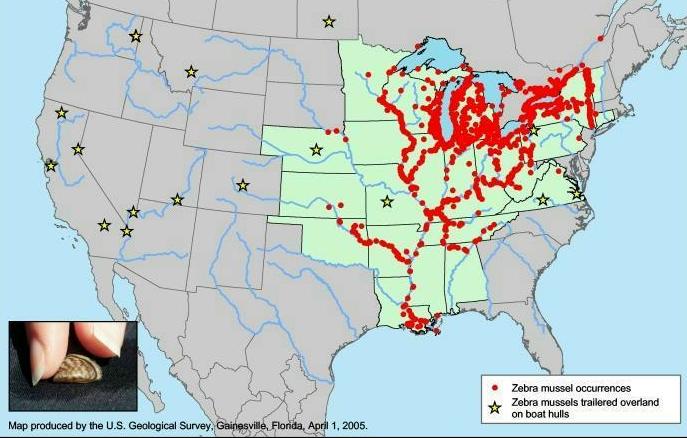

Map shows distribution of zebra mussels - the red dots are

sightings, the yellow stars are locations the mussels were

trailered to overland on boat hulls. U.S. Geological Survey

map published April 1, 2005. (Map courtesy USGS)

Zebra mussels have become a widespread aquatic

invasive species throughout the eastern United States since

they arrived in the Great Lakes from the Caspian Sea in ships’

ballast water around 1988. The tiny, fast growing striped

mussels have clogged the water pipes of electric companies and

other industries.

The costs of zebra mussel proliferation are now more than

$3 billion per decade, according to 2002 estimates by the

General Accountability Office. |